10Gbps Internet: Super Broadband’s Secrets

[ad_1]

Guys, I did it! I recently upgraded my home to a 10Gbps Fiber-optic broadband plan via Sonic. Yes, that’s 10Gbps Internet or ten times the speed of Gigabit.

And no, it’s not expensive, just $40/month (no contract required), which is very reasonable, if not cheap, in the USA. To put things in perspective, I’ve been paying almost double the amount for a Gigabit Comcast Cable connection.

So, where I live, in the San Francisco Bay Area, Sonic Fiber-optic is a great deal. I’d recommend it. And that’s the good news. The not-so-good is, well, there’s more, a lot more, to getting 10Gbps than just the broadband subscription.

This post will talk about that and set some expectations. But in a nutshell, 10Gbps is literally the Gigabit broadband ten times over.

Most importantly, this so-called “quest” for 10Gbps Internet is to satisfy my fabricated vain achievement — so I can say I’ve gotten that milestone. Above certain Gbps, the broadband speed makes zero difference in real-world usage.

Dong’s note: This post contains a referral link available to all Sonic Fiber-optic subscribers that gives the account holder some credit for new signups. This piece is not a review of the Internet service though it does include my real-world, hands-on experience with Sonic 10Gbp Fiber-optic broadband.

10Gbps Internet: Broadband is no longer the bottleneck

For years, the sub-Gigabit broadband connection has always been the bottleneck in our connection to the outside world — it’s still is for many, if not most, citizens of the world.

No matter how fast your Wi-Fi is, if your Internet is 100Mbps, then you can’t download anything faster than 100Mbps, on a good day.

Then we have Gigabit-class Internet — something that’s between 500Mbps to 1Gbps. But at the same time, we also have Wi-Fi 6 and Wi-Fi 6E that currently can deliver up to 2.4Gbps of local speed – that’s the current top-tier four-stream (4×4) at 160MHz — or Gig+ sustained real-world rates.

As a result, it’s always been incorrect to use an Internet speed test to gauge your Wi-Fi speed — chances are the former is the bottleneck. I ranted long and hard about that in this post on speed testing.

Data transmission speed in a nutshell

On a computer screen, each character, including a space between two words, generally requires one byte of data. One byte equals eight bits.

1,000,000 bits = 1 Megabits (Mb)

Megabit per second (Mbps) is the common unit for data transmission nowadays. Based on that, the following are common terms:

- Fast Ethernet: A connection standard that can deliver up to 100Mbps.

- Gigabit: That’s 1Gbps or 1000Mbps. It’s currently the most popular wired connection standard.

- Gig+: A connection that’s faster than 1Gbps but slower than 2Gbps. It often applies to Wi-Fi 6/E or Internet speeds.

- Multi-Gigabit: That’s multi-gigabit — a connection that’s 2Gbps or faster.

- Multi-Gig: A new BASE-T wired connection standard that delivers 100Mbps, 1Gbps, 2.5Gbps, 5Gbps, or 10Gbpsd, depending on the devices involved.

A 10Gbps — that’s 10 Gigabit Ethernet, a.k.a 10GE, 10GbE, or 10 GigE — broadband connection changes all the above. The Internet is now the fastest pipe in your home. But it also brings about other issues for those wanting to get the absolute most out of their connection.

The question is, how do we know we actually get 10Gbps? Let’s me break it right away: we can’t.

At best, we can only get close 10Gbps since the equipment has overhead, and 10Gbps is the highest ceiling speed grade any home router or switch can handle.

In other words, if you want to see a real 10Gbps sustained rate, you will need equipment that can handle 20Gbps or faster. Now that’s just too much.

And even when you just want a “sorta 10Gbps” connection. Things can be challenging, too. I speak from experience.

Let’s start with the hardware that I use.

10Gbps on the client end: Wired only, and it’s tricky

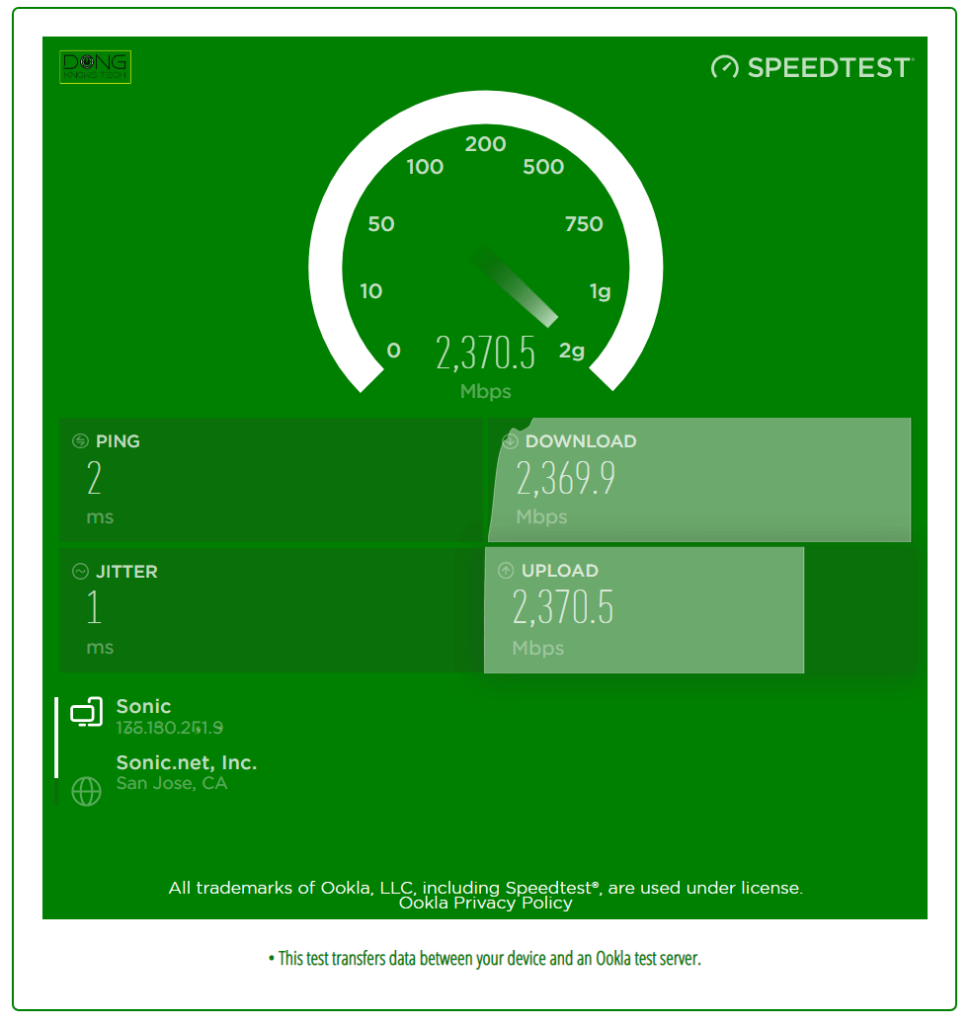

Above is a screenshot of my current Internet speed on my work computer. It’s fast, alright, but you’ll note that it’s not 10Gbps, but just about 2.5Gbps. Did I get ripped off? Nope.

My desktop computer used for the test — a relatively compact gaming machine powered by the Asus ROG Strix Z590-I motherboard — has a built-in 2.5Gbps Multi-Gig network adapter. And the Internet connection saturated that Multi-Gig connection.

Eventually, there will be a motherboard with a built-in 10Gbps network port. For now, the only way to get a 10Gbps on a computer is via a PCIe add-on Ethernet adapter.

That was not an option with my Z590-I since I already used its only qualified PCIe slot for a gaming graphic card.

Upgrading a desktop computer to 10Gbps Multi-Gig is similar to upgrading it to Wi-Fi 6/E. You get an add-on card, assemble it on a qualified PCIe slot and install the software.

The biggest and only difference is a 10Gbps NIC card requires a four-lane (x4) or faster PCIe slot instead of a single-lane (x1).

On most desktop motherboards, the only PCIe slot applicable is the 16-lane slot, generally reserved for a graphics card. In this case, you can only upgrade if you use the computer’s onboard video adapter.

How about Wi-Fi, you might ask?

As I mentioned above, even the best-to-date Wi-Fi connection can’t go over 2.4Gbps of ceiling speed, which translates into Gig+ sustained real-world speed. So it’s virtually impossible to experience 10Gbps via Wi-Fi — not even a quarter of that.

When (or if) 4×4 clients are available, we’ll get some 4.8Gbps of ceiling speed out of Wi-Fi, still less than half of 10Gbps.

So, if you want to experience 10Gbps, upgrading your computer to a 10Gbps wired adapter is the only way for now. And for my testing, I’ve had a couple of machines running these adapters for a few years.

But even then, that’s only half of the equation. You need a router and possibly a switch of the same caliber, too.

10Gbps Internet on the router end: Limited options

There are about two dozen of home Wi-Fi routers that come with Multi-Gig wired capability. And, not to brag, I’ve reviewed them all except for the latest eero Pro 6E, which I deliberately avoided.

Of those, there are just four that are 10Gbps-capable. (Hit the button below to view their ratings and review links). The rest can only handle the 5Gbps or 2.5Gbps speed grades and are clearly out of the question in this glorious quest.

Extra: Current 10Gbps-capable Wi-Fi routers

Home Wi-Fi routers with 10Gbps wired capability

Below are the current four home Wi-Fi routers that are 10Gbps-capable, in review order with the latest on top.

Netgear Orbi RBKE960 Series: 10Gbps Multi-Gig WAN + 2.5Gbps Multi-Gig LAN

Pros

Powerful hardware with Quad-band Wi-Fi and Multi-Gig wired backhaul support

Excellent Wi-Fi coverage, fast performance

More Wi-Fi networks than previous Orbis, including two additional virtual SSIDs

Cons

No web-based Remote Management, few free features, Mobile app (with a login account and even subscriptions) are required to be useful

Rigid Multi-Gig ports’ roles, few Multi-Gig ports

The 2nd 5GHz-band is unavailable to clients even with wired backhauls, no 160MHz channel width on 5GHz

Limited Wi-Fi customization, bulky design

QNAP QHora-301W: Dual 10Gbps Multi-Gig ports

Pros

Reliable Wi-Fi performance

SD-WAN and other enterprise-class features

Cons

Expensive for the modest Wi-Fi coverage

Some common settings are missing

No real Dynamic DNS, QoS, and Parental Controls

Useless USB-related features

Zyxel Armor G5: 1x 2.5Gbps WAN + 1x 10Gbps LAN Multi-Gig ports

Pros

Two Multi-Gig network ports

Cons

Overall buggy, especially the USB-related features

Severely lacking in features: Not mesh-ready, no Dual-WAN, no Link Aggregation, no QoS

Parental Control is a joke

Asus RT-AX89X: Dual LAN/WAN 10Gbps (Base-T and SFP+) ports

Pros

Excellent Wi-Fi performance

Uniquely cool design with two 10Gbps network ports

Eight Gigabit network ports with Dual-WAN and Link Aggregation

Super-fast network-attached storage speed when coupled with an external drive

Tons of useful features, including free-for-life real-time online protection and AiMesh

Cons

A bit buggy at launch, relatively expensive

Bulky physical size with an internal fan — potential heat issue in hot environments

Not wall-mountable, no universal backup restoration

Of the four above, only the Asus RT-AX89X and QNAP QHora-301W have two 10Gbps ports — we’d need one for the WAN connection and the other for the LAN side.

Considering the Asus is a much better router in terms of hardware specs and features, I decided to go with it.

(Out of curiosity, I also used the QNAP briefly, and it delivered a similar 10Gbps experience as described below.)

The RT-AX89X has two 10Gbps ports. One is a Multi-Gig (Base-T), and the other is an SFP+.

The Fiber-optic ONT Sonic put in my house, like most ONTs, used a Base-T RJ45 port, so I used the router’s 10Gbps Multi-Gig port for the Internet connection. The WAN side was straightforward.

Extra: BASE-T vs SFP+

The BASE-T (or BaseT) port type refers to the wiring method used inside the network cable and the connectors at its ends, which is 8-position 8-contact (8P8C). This type is known via a misnomer called Registered Jack 45 or RJ45. So we’ll keep calling it RJ45.

But there’s also SFP or SFP+ (plus) port type, used mostly for enterprise applications, that’s different physically but has the same networking principles as Base-T. SFP stands for small form pluggable and is the technical name for what is often referred to as Fiber Channel or Fiber.

An SFP+ port has speed grades of either 1Gbps or 10Gbps — the older version of SFP can only do 1Gbps. The two share the same port type. That’s all you need to know about SFP. Base-T is the more popular by far.

Generally, you can get an adapter to use a BaseT device with an SFP or SFP+ port. Still, in this case, compatibility can be an issue — a particular adapter might only work (well) with the SFP/+ port of certain hardware vendors.

On the LAN side, things were a bit more complicated. I had no computer with an SFP+ port and didn’t want to get an adapter. That, plus the fact I’d like to use more wired Multi-Gig devices, meant I’d need a switch.

10Gbps-capable switches: Still very expensive

While Gigabit switches are a dime in a dozen and relatively affordable, Multi-Gig switches, especially those capable of 10Gbps, are still scarce. And they are all expensive.

And I needed one that has an SFP+ port. Of all switches I’ve reviewed, the Zyxel XS1930-12HP is the only one that fits the bill, so I used it — I’ve always used it, and a couple of others, since their reviews, to tell the truth.

If you wonder, this switch’s current price is around $1000, and it’s less expensive than many of its peers.

There are more affordable Multi-Gig switches, but they have mostly lower-grade ports (2.5Gbps or 5Gbps).

It’s worth noting that all switches have overhead, and the Zyxel didn’t deliver the full 10Gbps in my testing. The chart above shows the performances of all Multi-Gig switches I’ve reviewed.

That said, so far on the equipment front, I’ve used the following:

I’ve gotten these devices for review and testing purposes over time, but if you buy them today, that’d cost you some $2000.

(What I haven’t told you yet is I also used a pair of ZenWiFi Pro ET12 as my Multi-Gig Wired mesh satellites. These have a 2.5Gbps WAN port for the incoming wired connection, not as good as 10Gbps but still faster than any Wi-Fi link. I’m nuts when it comes to networking, if you haven’t noticed.)

And that brings us to my actual Internet speed out of my 10Gbps Fiber-optic broadband, using this souped-up set of equipment.

My real Multi-Gig Internet speed

Upon completing the installation, the friendly Sonic tech did a test at the ONT with his special equipment.

“8 gigs down and 5 gigs up,” he said, “It’ll probably get faster once the ONT has been updated. Give it a day or two. It’ll be different.”

And he didn’t lie. During the next couple of days, using the equipment listed above, I generally got speeds between 6Gbps to 8Gbps in both directions.

Those weren’t exactly 10Gbps but, to be fair, they might have been the speed of any of the parts involved, be it the router, the switch, or the network adapters. Also, I wired part of my house with CAT5e, which can do 10Gbps but not as well as CAT6 or higher-grade cables.

In any case, I could eliminate the go-betweens and other devices that might be using the broadband connection by connecting one of my 10Gbps-capable desktops to the ONT directly to do a real test. And I did think about that.

But the idea proved to be too much work due to the layout of my home. Among other things, I couldn’t run long cables willy nilly and risk having my children, or worse, my wife, tripping over them.

Most importantly, I didn’t care. Even on my office “work” desktop mentioned above, 2.5Gbps is already crazy fast — that’s more than 2.5 times the speeds of Comcast on the download pipe and hundreds of times faster on the upload. Anything above that is ridiculous.

And “I don’t care” is my actual new Internet speed. You know, that level when you’ve already turned things up way past 11. You probably wouldn’t bother either.

Fiber-optic broadband is so much better than Cable, by the way. The speed aside, I consistently get ping and jitter values — those that determine the quality of a connection — below a few milliseconds. In many tests, they were at zero.

My Comcast Cable connection generally has pings at 15 milliseconds and imposes a monthly data cap of 1.25 terabytes — I receive that dreadful message saying I’ve almost used up my limit practically every month.

Sonic has no monthly data cap, and with that comes the feeling of freedom. Now, I don’t care about my Internet usage because I don’t need to.

Multi-Gig Internet and its hidden benefits

10Gbps or not, my broadband connection is now easily in the Multi-Gig realm. The crazy speeds, apart from being, well, fast, also brings in some benefits that you can’t have with sub-Gigabit.

QoS is (mostly) no longer applicable

The first is probably the fact that you don’t need to use Quality of Service anymore. I wrote about QoS in this post, but it’s a function that prioritizes the broadband connection to prevent a device from hogging all the bandwidth.

Considering most devices has Gigabit or Wi-Fi at best, the network adapter itself is now the bandwidth guardrail. For example, if you host a BitTorrent client on a computer with a Gigabit connection, the client can’t use more than 1000Mbps of Internet bandwidth anyway.

Supposedly, you still have some 9000Mbps for other things — it’s a matter of bandwidth. If you use multiples clients like that, then it might still be a good idea to use QoS. But you get the idea.

Bandwidth vs speed

When it comes to a data connection we tend to think of speed, as in how fast data move from one party to another, generally measured in bits per second.

For a slow connection, we use kilobit (Kbps), for faster ones, we use megabit (Mbps) or Gigabit (Gbps).

When you get a broadband plan, the number of bits also indicates its bandwidth. A Gigabit plan (1000Mbps) allows two devices to connect at 500Mbps simultaneously. With a 10Gbps plan, you can do that on 20 concurrent 500Mbps-capable devices.

That’s why fast broadband is still applicable when there are only slow devices within a network.

And by the way, in my case, the Fiber-optic also improves real-time communication a great deal, likely thanks to the better connection quality mentioned above.

A bit of digression: I almost busted laughing seeing what Sonic offered as Wi-Fi equipment for its 10Gbps Internet. The mentioned hardware can’t even deliver Gigabit of real-world speed! So it could be any worse of a choice, which was why I made the screengrab. But the initial doubt about the provider’s real broadband speeds slowly melted away after over a week of real-world experience.

A new level of personal server

Thanks to the much faster upload speed, you’d note that all personal remote server applications work much better.

My business partners and I use several Synology NAS servers in multiple locations and sync data between them as off-site backups. The super-fast broadband — and the omission of a month data cap — makes this much better. At least on my end.

And if you use a personal media server, such as Plex, content streaming from a remote party is now just like using Netflix or Hulu in terms of speed and video quality. Actually, it was better in my trial.

The Internet speed test is now applicable for local Wi-Fi testing

This part applies directly to what I do on this website. From now on, I can confidently use the Internet as the base to test local Wi-Fi, and I’ve tried that with the Netgear WAX630E.

I’ll keep my current test methodology but knowing that the Internet is no longer the bottleneck will make my work much easier.

Among other things, I’ll be able to determine if a router is consistent on both LAN and WAN sides, if its WAN port is truly Multi-Gig or not, etc. Rest assured that I’ll add this new information in future reviews.

The takeaway

Again, it’s impossible to get a real sustained 10Gbps connection — we need faster equipment to have that. It was likely for that reason, Sonic told me that my broadband was “up to” 10Gbps.

And so far, that proved to be a genuine promise. And for the most part, again, I don’t really care if it’s truly 10Gbps at all times — it’s probably not — because, well, check the dictionary for the meaning of the word “saturation.”

So 10Gbps broadband is great. It’s super-great, in fact, if you can get it without sacrificing your arm or your leg. But be aware of the hidden costs if you want to truly experience all or even just most of it — chances are you can’t no matter what.

But ultra-fast broadband is still nice — or it doesn’t hurt — if you keep your existing Gigabit equipment.

In daily usage, though, any Internet connection faster than 1Gbps makes no difference in all cases — the remote party or those in between them and your home will be the bottleneck anyway.

The 10Gbps pipe only means you can have multiple Gigabit connections simultaneously. And if something is slow, you can say with confidence “it’s the other guy!”

As I said before in the post about Gigabit Internet, it’s not how fast a connection is but what you do with it that matters. The point is that you should appreciate and make the most of what you have. A 10Gbps connection put the latter a bit upside down — don’t kill yourself trying to make the most out of it! There’s no need to.

Speaking of making the most, I’ll still keep my “slow” Gigabit Cable connection for now. Dual-WAN has its unique benefits, and that’ll be another story. Stay tuned!

In the meantime, if you’re curious about how fast your Internet is, hit the Go button below to find out. And don’t be jealous!

• This test transfers data between your device and an Ookla test server.

[ad_2]

Source link